"I'm sorry, I got ahead of myself. Hi there, you on the table. I wonder if you'd mind taking a brief survey..."

Anyone anywhere who has taken a biology class will be familiar with Carl Linnaeus' system of “binomial nomenclature” where organisms are identified with a name composed of two parts. The first identifies the genus and the second identifies the actual species - Canis familiaris, Carcharodon carcharias, Gorilla gorilla, Poa alpina - all examples of how this system operates.

One way of visualising biological taxonomy, where each higher tier branches off into several lower tiers until terminating at species.[2]

If this if enough for you, feel free to leave now and go do whatever you wish with your life. For those who remain, you understand that modern taxonomy is significantly more complex than a system from the mid-1700s. The core concept is that genera with shared characteristics can be grouped together as a family. Families with shared characteristics can be grouped together as an order and so on and so forth.

Continue this for a spell and now you have constructed a biological classification system consisting of species organised into genera organised into families organised into orders organised into classes organised into phyla organised into kingdoms and finally organised into domains.[1]

For the extreme pedants out there, you could, if you so wish, describe every organism from its domain to its species - for any cat, tree, trilobite, mushroom and human.

Tonight, I am that extreme pedant for the latter.

Domain

In the utmost broadest terms, humans are members of the Eukarya, which they share with every other form of life excluding the Bacteria and Archaea. Their distinctive characteristic is that their cells have a membrane-bound nucleus, which is important for containing the cell's genetic information.[3]

The eukaryotes arose because of an endosymbiosis event, where an ancestral Archaean engulfed a bacterium to give rise to the first eukaryotic common ancestor. A key innovation of this process was the mitochondria organelle which releases energy from organic compounds for its organism to utilise.[4]

Kingdom

Within the Eukarya are several kingdoms and, to no surprise, humans are members of the Animalia. The key characteristic is that animals are multicellular, often to the extent their cells are just a small component of complex organ systems. Animals move around during their lifespan, produce gametes in order to sexually reproduce and breathe oxygen (know that Earth is the only known planet with free oxygen in the atmosphere).

Dickinsonia was a member of the Eidicarian biota and yes it was that flat.[6]

Now an origin for animals depends on who you ask. Personally, I adore the Ediacaran biota, creatures that lived on Earth shortly before the Cambrian explosion and are famous for their bizarre morphologies. Morphologies that oftentimes seem to blur the line between animal and plant, such as those with bizarre fractal growth frond morphologies.[5]

Phylum

Phyla are unique body plans, for animals almost all originated during the Cambrian Explosion. Luckily for life this explosion was more of a boom in biodiversity than a literal boom in dynamite, resulting from a combination of preceding factors such as the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia.[7]

My favourite fossil deposit, the Burgess Shale of British Columbia, preserves the results of this event in exceptional clarity. A fossil of importance for us here is Pikaia gracilens, the earliest known member of our phylum the Chordates.[8] A chordate's key characteristics are its bilaterian nature (a human is symmetrical for the most part), possession of a notochord, a hollow dorsal nerve chord and pharyngeal slits.[9]

Class

“Mammal” is certainly a term incredibly familiar to anyone who has read this far, if it isn't then I'm incredibly fascinated by your life. Regardless, a mammal is a vertebrate predominantly recognised by milk production and fur or otherwise hair.[10]

The Palaeogene period followed the Cretaceous and was characterised by a diversification and radiation of mammals. The end-Cretaceous extinction is easily the most well-known due to the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs, which was primarily caused by the Chicxulub impact and eruption of the Deccan Traps. Therefore, the niches previously occupied by those dinosaurs were now free for mammals to evolve into.[11]

Order

We taught this Chimpanzee to understand isotope geochemistry and he hanged himself.[13]

From here on out we really start to see where significant human qualities originate, as primates exhibit many of them. Large brain sizes become most revolutionary down the line, but there is also binocular vision allowing us to accurately judge distances, vocalisations that eventually allow for languages to develop and opposable thumbs that offer much greater dexterity especially when it comes to tool use.[12]

From a more aesthetic or morphological viewpoint, the level of primates is when animals are becoming properly “human-shaped”, especially the simians.

Family

The great apes' proper name is the Hominidae who are fundamentally just tailless primates. So I will move on.[14]

Genus

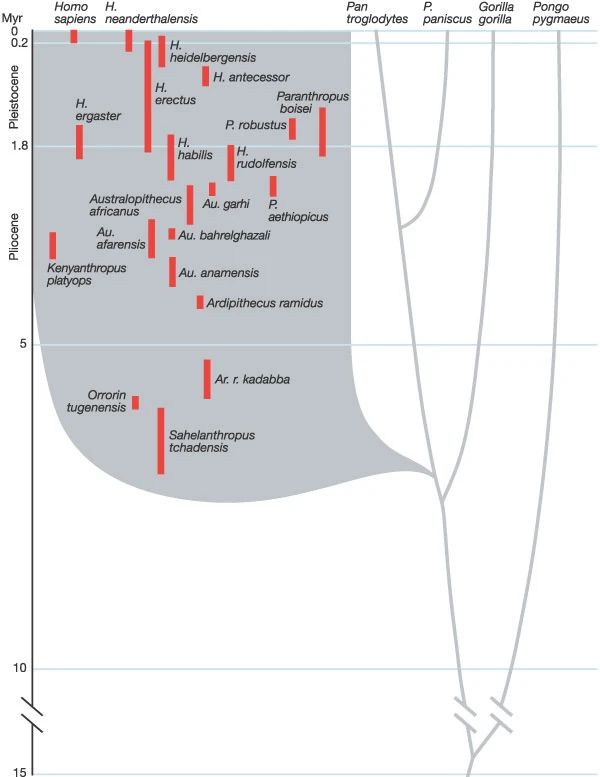

Tree showing the temporal ranges of archaic humans and how they diverged from a common ancestor to apes.[16]

Now we're back down to the first half of binomial nomenclature, however we are the only extant species of the homo genus. Since their origin in the late Pliocene, there have existed a fascinating array of “archaic humans”.

If you were to observe a conga line of these “humans” from oldest to youngest you would notice an almost stepwise acquisition of human characteristics; they would start to walk more upright on two feet, have larger and larger brains with denser neurons, the emerging use of tools, changes to teeth and jaws and cheap souvenirs[citation needed] as Homo erectus along with later species began to migrate across the world.[15]

Species

To be sapient is to possess great wisdom and discernment, the two key qualities resulting in sapiens' rise to dominance across the globe in merely 300,000 years.

Discussion of the uncountable achievements throughout that time is far outside the scope of this article and my own understanding, but what else besides "sapience" makes us so successful? Frankly, the simplest way to describe it is we did everything that every other Homo did but better.

We are by far the most intelligent and cognitively advanced species on the planet which is the entire reason we have been able to construct human civilisation, the computer could never have been made without someone's really great grandparent making a sharp enough rock.

So, if you, extreme pedant, ever wanted to taxonomically classify any human from today, yesterday, or when we emerged 300,00 years ago, just remember that we're a Eukaryotic Animal Chordate Mammal Primate Hominidae Homo Sapiens.

Citations

- [1] https://www.britannica.com/science/taxonomy

- [2] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Biological_classification_L_Pengo_vflip.svg

- [3] https://www.britannica.com/science/eukaryote

- [4] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4571569/

- [5] https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.earth.33.092203.122519

- [6] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DickinsoniaCostata.jpg

- [7] https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.earth.33.031504.103001

- [8] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00220.x?casa_token=tbA2By7ryBAAAAAA%3AnKeizp2dzv31xgK4BSpFzUaMmkCS6bhN7mlXb-xVuIZopy4PuQBeKZ_tstLMiZj69UrBaJma_LSv0Bo

- [9] https://www.britannica.com/animal/chordate

- [10] https://www.britannica.com/animal/mammal

- [11] https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.1229237

- [12] https://www.britannica.com/animal/primate-mammal

- [13] https://www.nature.com/articles/nature01495

- [14] https://www.britannica.com/animal/Hominidae

- [15] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/bies.950181204?casa_token=bcUBd34vlgYAAAAA%3Axo5zWKLV2xNA4UyEn-54dJxYR-B2kCO1OqV78XpsNKexIQkJiUdIPqUPQWKOgWibrYWZb_n7bydM8fA

- [16] https://www.nature.com/articles/nature01495